Share this Post

Digital platforms, namely social media platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, and TikTok, have been constructing and facilitating social discourse for over a decade. These platforms are hubs where users share political views, discuss global health responses, organize protests, and, more than ever, consume news. Despite their immense and undisputed power, however, these platforms were virtually free of regulatory oversight until the end of the 2010s. In over 60 countries and jurisdiction legal immunities, such as Section 230 in the US and the E-commerce directive in the EU, safeguarded platforms from liability for user content. This ensured companies would not face legal repercussions for content found on their platform, or be required to monitor for illegal or problematic material. The state could not prosecute them; citizens could not sue them. In practice, these immunities gave platforms unlimited discretion to determine what is allowed and disallowed online.

Until 2022, these regulatory liability regimes remained nearly intact; today, however, the global legislative climate is rapidly changing. Legislators in many countries are now trying to find common ground on rules that would expand platforms’ responsibilities toward users, regulators, and society. The reasons for this are plentiful, and different developments incentivize different stakeholders. Somewhat ironically, while a consensus has evolved around how to characterize the root of the problem – the need for regulation of online platforms – opinions about the nature of the problem vary greatly.

For many, a growing list of examples where online discourse led to real-world harm, from rising suicide rates among teens to the link between polarization in society and political upheaval, became the primary motivation to support the notion that platforms should do more to remove harmful content uploaded by users. Public confidence in platforms’ willingness to do so without regulatory oversight was never high, but following revelations such as those exposed by Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen, it plummeted even further. On the other side of this debate, decision-makers are similarly concerned about the role of online platforms in social life, but from a different angle. For them, the core issues stem from companies’ complete discretion in deleting content, opening the stage to censorship by private corporations with no public oversight. If a platform is in any case immune from liability for uploaded content, so this logic goes, it should not have discretionary power to control content.

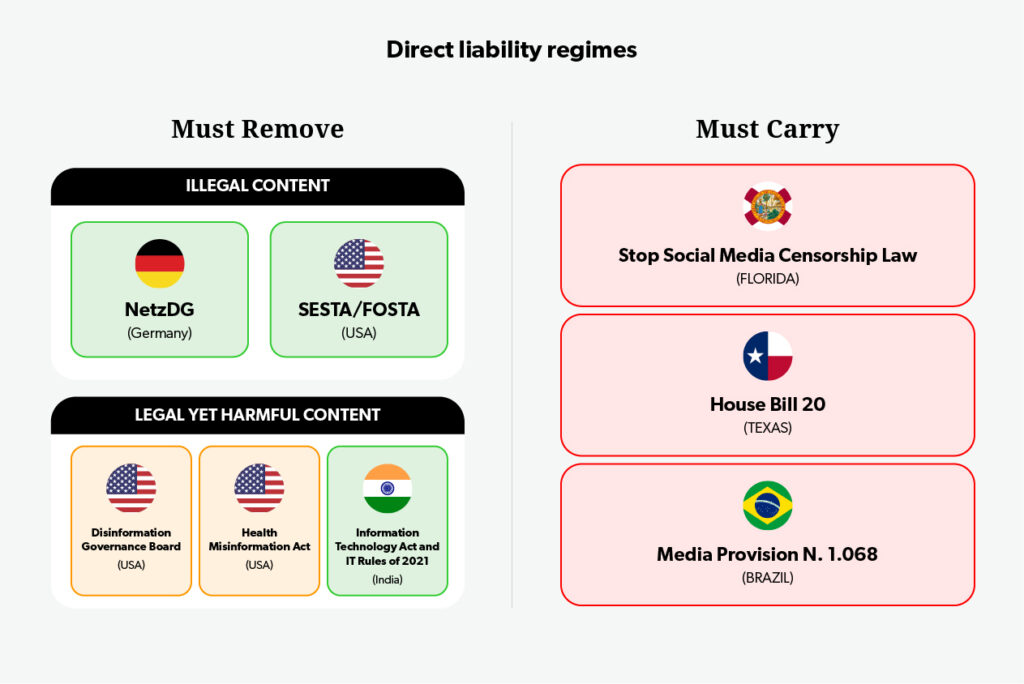

Variations in the understandings of the problem has long meant that the consensus about the negative role of online platforms has not translated into an agreement regarding solutions. Those concerned with the harm caused by existing content began developing “must remove” liability regimes, while those worried about platform deletion promoted “must carry” regimes; both sides overlooked critical difficulties with each approach. Just as deadlock seemed inevitable, however, the EU began to pave the way forward, rejecting the binary “must remove”/“must carry” debate, and offering an alternative.

“Must Remove” Illegal Content Regimes

For regulators most concerned about the dangers posed by uploaded content, the immediate response seems straightforward: Removing platform immunity from criminal liability for harmful user content uploaded, propagated, and shared online. This applies first and foremost in cases where such content is illegal, such as non-consensual pornographic material, but also extends to liability in instances where content is legal, yet dangerous when amplified on social media. Examples of such material include content that promotes teenage eating disorders or propagates disinformation about political events.

In practice, advocates of “must remove” illegal content regimes encounter substantial opposition, on the part of both platforms and users. The German NetzDG Act, which took effect in January 2018, and the US FOSTA/SESTA bills reveal why. The former requires platforms to remove illegal content within seven days of receiving a report, or 24 hours in “clearly illegal” cases, while the latter limits the immunities accruing to platforms under Section 230 of the United States Code for reported content relating to sex trafficking.

From the perspective of the platforms, these laws create an operational nightmare, requiring them to monitor every piece of content and determine its legality within a very short timeframe. Even when immunity is removed only for violative content reported to the platform, as is the case in the abovementioned laws, monitoring requirements might be limited but the reports create an immense burden on platforms which will have to examine thousands of cases in very short, rather unrealistic, periods of time. Unavoidably, the result is swift prosecution that fails to take practical considerations into account. Advocates of user rights, on their part, are also deeply concerned about “must remove” laws. For them, these laws are de-facto authorizations for platforms to act as judges, solidifying a reality where user violations in posting unacceptable content are determined by a non-state, non-public entity instead of by a judicial court bound by democratically enacted laws, and due process.

Advocates of user rights further warn that such a regime creates a “chilling” effect that limits speech beyond what is bound by law. In a “must remove” illegal content regime, platforms are not fair judges. They are incentivized to err towards removing more material than necessary, in order to avoid even the slightest risk of it later being deemed illegal in a court of law. This, in turn, incentivizes users to limit their speech to avoid online sanctions and account removal. The reaction to the FOSTA/SESTA bills, demonstrates one instance of this situation and its consequences: While the legislation was intended only to prevent content related to sex-trafficking, it led to excessive removal by platforms of sex worker and stripper ads, resulting in these workers looking for clients in other, highly dangerous, online and offline marketplaces. Regardless of how one perceives the morality and question of legalizing these professions, FOSTA/ SESTA made it clear that if regulators require platforms to remove specific illegal content, a certain amount of legal material will be removed as well, and users will be hesitant to challenge the limits.

“Must Remove” Legal Content Regimes

Given the abovementioned concerns of both platforms and civil rights advocates with “must remove” regimes for illegal content, it might seem surprising that some countries are considering expanding such regimes to content that is not illegal, but is considered harmful, such as bullying between children, vaccine misinformation, and political disinformation. These efforts suffer not only from the same “chilling” effects described above, but also add an additional level of concern, since they are implemented through an agency, usually politically appointed, that is vested with determining what content is harmful without having to go through traditional legislative oversight. In cases where the content is closely related to electoral or inherently political issues, this can become a powerful tool for de facto governmental censorship of opposing voices. Predictably, global democracy watchdogs consider legislation of such laws a sign of democratic erosion.

Most prominently, throughout the Covid 19 pandemic in India, such laws raised great concern among digital rights advocates. During the country’s surge in cases in early 2021, the Indian government, claiming it was acting against platforms that did not quickly remove pandemic misinformation, sent police forces to raid Twitter headquarters and force the platform to comply with “must remove” requirements. The non-complying “misinforming” content found on the platform included WHO-approved facts about Covid-19 variants, criticism of the government for underreporting deaths, and vaccine distribution data confirmed by leading international newspapers. In a related example, laws of this kind were used by Russia to justify Moscow’s decision to block access to Facebook and Twitter following the invasion of Ukraine in January 2022.

Elsewhere around the globe, proponents of “must remove” laws believe that these cases should not be compared to their “well-intended” attempts. In their view, the Indian and Russian examples were cases where censoring opposing voices was the motive behind the law, not an accidental side effect. If regulators’ intentions are honest, proponents argue, there is no reason for alarm. Regardless of the intentions behind passing such laws, however, the powers given to governmental agencies remain the same. The potential for immediate or future abuse in a liberal democracy, then, is as real as in the most autocratic country.

In July 2021, Democratic Senator Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota introduced a bill to remove platforms immunity under Section 230 for harms stemming from health-related misinformation. The bill did not set qualifying criteria for such content, leaving that responsibility to the Secretary of Health and Human Services, a political appointee of the president. Ultimately, the law did not proceed through Congress when Klobuchar’s fundamentally progressive intentions coincided with the prospect of an impending Republican administration that might use such legislation to further an opposing agenda of defining truth and falsehood regarding Covid-19 and other health crises. Similarly, in April 2022, the White House announced it would create a “Disinformation Governance Board” under the direction of the Department of Homeland Security. Criticism, from left and right, of the immense power such a body would have as an arbitrator of online truth led the Biden administration to reverse its decision within less than three weeks.

“Must Carry” Regimes

Regulators who believe that most harm caused by online platforms results from the content they take down, not what they leave up, maintain the position that companies should not be able to remove speech without due process. This position is predicated on a regard for the wide-ranging influence of social media and the necessity of protecting it as a free speech space. Objectionable content, they believe, is not a matter for Facebook to decide; without a court order, there is little justification for content removal, especially political and electoral content. In Florida, supporters of a “must carry” regime led to the “Stop Social Media Censorship Law,” a regulation prohibiting platforms from removing content uploaded by an elected official or political candidate. The law closely resembled a Brazilian regulation used by President Jair Bolsonaro to prevent the removal of governmental posts promoting questionable Covid-19 cures. The law was later struck down by the Brazilian Supreme Court.

As of July 2022, the Florida law was blocked by a federal court and deemed unconstitutional. The US Constitution’s First Amendment, which prohibits the government from intervening in private entities’ Freedom of Speech, safeguards an entity’s right to decide what to express, and this includes the right to decide what they do not want to express. As the law currently considers online platforms as private entities, just like any other company or citizen, this logic applies to them as well. In other words, “must carry” laws were deemed unconstitutional because they demand that platforms carry specific types of expression, infringing on their speech rights just as much as a law that would shut them down based on the speech they carry.

The fate of a Texas “must carry” law, that goes further than its Floridian counterpart, seems to be heading in the same direction. Instead of focusing on political content, the law prohibits the removal of any material whatsoever, from political content to spam and scams. In May 2022, the US Supreme Court blocked the law pending further legal proceedings. Platforms warn that regardless of constitutionality, this law would have dire effects on social media because the vast majority of content removed today by platforms is universally undesirable. If people want to continue using online platforms to interact with friends, says this position, they should oppose this law that would swamp their news feeds with unmarked ads for fake diet pills and Social Security fraudsters.

Red – blocked by courts; Green – legislated and enacted; Orange – in legislative procedures.

The Indirect Approach

Both “must remove” and “must carry” laws try to directly impact moderation decisions of online platforms by limiting their discretion. Each of these regimes has a group of avid supporters who dismiss concerns of democratic and human rights erosion in the opposing position, and explain why the opposite direct intervention regime is dangerous and messy. Clashes between both camps are inevitable and make it virtually impossible to reach a political consensus promoting either approach.

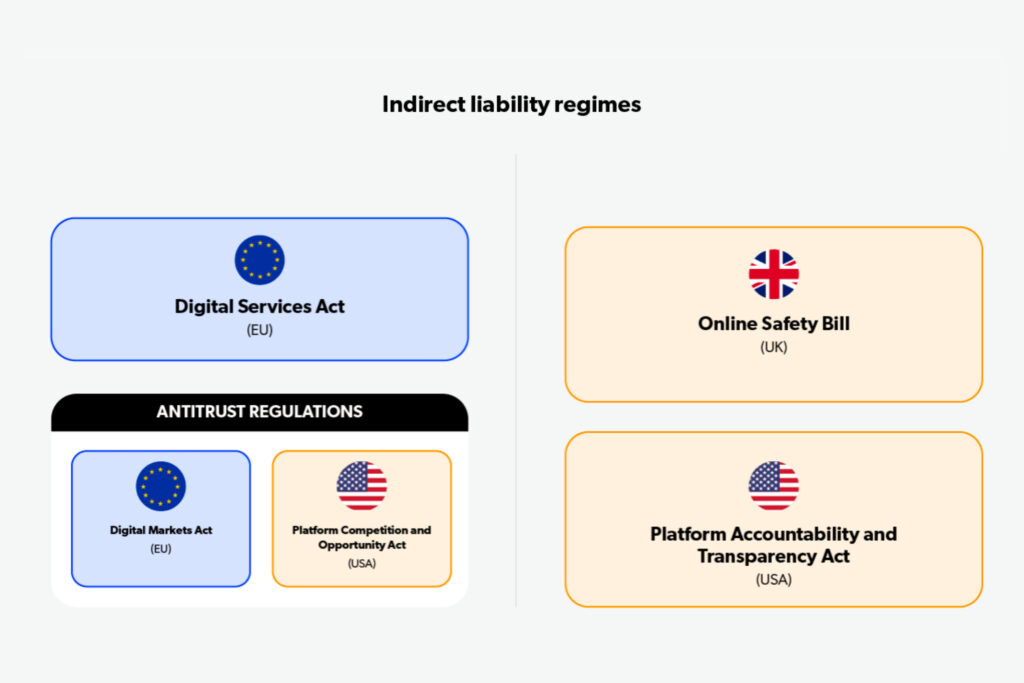

To achieve progress despite this deadlock, legislators have begun to consider indirect modes of intervention. Unquestionably, the EU is leading these attempts, and in January 2024, the Digital Services Act (DSA), a first-of-its-kind indirect intervention regime, will come into force. At its core, the regulation attempts to shape platforms’ moderation practices by increasing their accountability to the public. Instead of eliminating platform liability for keeping or removing specific content, the DSA would impose substantial fines on platforms that do not abide by basic best practices which would allow the public, and regulators, to scrutinize their behavior.

Among its main clauses, the DSA requires platforms to conduct annual risk assessments of their products and report to regulators what measures are taken to reduce risks, especially for platforms used by younger audiences. Aside from manifestly dangerous situations, regulators will not be able to penalize companies for specific moderation decisions, but they will have the power to fine companies that have not taken sufficient steps to minimize undesired harms. A similar approach is currently endorsed in the UK Online Safety Bill, which, as of July 2022, has yet to pass fully into legislation.

In addition to risk assessments, the DSA requires platforms to increase transparency through annual public reports, clarifying Terms of Service and Community Standards, and providing users whose content was removed or otherwise limited with an explanation and an effective path for appeal and redress. Platforms will also clearly label advertising content and publish a database of each advertiser’s current and past online ads.

For EU legislators, the appeal of the DSA mechanism is in its subtlety. Instead of choosing a side in the debate on whether platforms should censor specific opinions or refrain from removing harmful content, the DSA ensures that the public has the tools and information needed to scrutinize a platform’s practices. Perhaps that is why the regulation passed its last stage of legislation with overwhelming, cross-party support in the European Parliament. In the US, a group of legal scholars introduced a similar, albeit narrower, proposal, the Platform Accountability and Transparency Act, which would require platforms to share data with approved academic institutions. In a rare precedent for recent digital platform regulation in the US, it is promoted by a bipartisan group of legislators.

Blue – legislated; Orange – in legislative procedures.

Whether increasing public scrutiny is enough to create safer social platforms remains to be seen. Supporters of this indirect approach believe that it is the safest way to increase platforms’ responsibility without the risks of direct governmental intervention. Improved transparency will undoubtedly increase companies’ attention to the negative impacts of their platform. However, it is unclear how improved public scrutiny will help keep platforms in check as long as the social media market is still highly consolidated. Users have little choice, given the dominance of a small number of select mega-platforms. For this reason, even the strongest supporters of the indirect approach agree that an effective indirect regime must be coupled with an overhaul of antitrust laws to ensure increased competition in the digital platform market. The EU is already demanding cross-platform interoperability in its Digital Markets Act (DMA), making it easier for users of one platform to communicate with users of a competing product, and even in the US, an antitrust regulation, the Platform Competition and Opportunity Act, is gaining traction. Such laws would augment indirect moderation regimes by ensuring that consumers have a choice and thus that companies have a market incentive to make their platforms safer for society.

The opinions expressed in this text are solely that of the author/s and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Israel Public Policy Institute (IPPI) and/or its partners.

Share this Post

Understanding Ocean Governance in Israel

Last year, Hendrik Schopmans participated in the Fellowship program of the Israel Public Policy Institute (IPPI) in cooperation…

What is 5G?

Why does 5G network technology matter? The fifth-generation cellular network technology, 5G, is about to accelerate the overall pace of…

The Renovation Wave: The Issue of Home Renovations in Addressing Energy Poverty

Energy poverty, also known as ‘fuel poverty’ or ‘energy insecurity’ in the US, has long been perceived as a…