Flying high? Unmanned aircraft and the future of transportation

Share this Post

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) and unmanned aircraft systems (UAS), commonly termed ‘drones’, have the potential to become some of the most influential and iconic technologies of the 21st century. Combining the capabilities of autonomous flight and advanced methods of data collection, drones are believed to provide an unprecedented tool for achieving more cost-effective, time-efficient, and safer processes. These capabilities – previously a privilege reserved for the military – are now increasingly incorporated into civilian domains, where drones create various applications ranging from surveillance and sensing missions to novel forms of last mile logistics and passenger transportation.

The use of unmanned aircraft has already become commonplace in agriculture, infrastructure maintenance, and search and rescue operations; in contrast, their application as a mode of transportation is still in its infancy. Prominent early cases of drones’ commercial use for delivery, for instance that of medicines and vaccines in Ghana and India; of laboratory samples in Switzerland; of food and consumer goods in the US, Australia, Iceland and India. The list of worldwide applications for drone delivery is growing rapidly, especially in light of delivery drones’ potential for supporting the public health system during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Depending on their technological specifications, electrically powered delivery drones can lift weights in the range of 1–8 kg, and can conduct flight missions in a range of 10–50 km. They can be employed in either mobile (combined with conventional delivery vehicles) or stationary systems.

Another type of unmanned vehicles is passenger drones, often referred to as ‘air taxis’. These cutting-edge electric aircraft can conduct vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) missions; and have the capacity to carry 1–5 passengers. Their flight range typically falls between 25–100 km, although some models’ range exceeds 250 km. Initial test flights in Singapore, Abu Dhabi or Stuttgart have been conducted to demonstrate drones’ technical capacity to transport passengers within or even between cities.

Various manufacturers and service providers (e.g. UBER), encouraged by numerous market forecasts of high production volumes and lucrative business opportunities, are currently pushing for an early market launch. The German manufacturer Lilium is planning to start selling its aircraft from 2025. Another German-based company, Volocopter, even plans to offer commercial flight services within the next few years. More realistically, analysts predict that air taxis won’t become economically viable before 2030.

Despite current uncertainty regarding the prospective timeframe for the growth of the transportation drone industry, there is a growing (political) consensus that delivery drones and air taxis will enjoy a bright future. If true, recent developments mark not just a historical turning point in aviation, but the beginning of a new era in which low level airspace may become the ‘third dimension’ of transportation.

The progress of unmanned aircraft technologies, framed in terms of urban air mobility (UAM) or vertical mobility, may not only serve as a disruptor for logistics and passenger transportation; it could also significantly influence society and public perception, as our conventional notions of space use will be extended to include the sky. Such an extension could have unprecedented economic and societal benefits, but also unknown environmental and social consequences. From a sociotechnical point of view, drones are a comparatively invasive technology with a multitude of potential side effects that range from possible negative impacts on the environment environmental conflicts to potential privacy infringements. Consequently, the pace of drone technology development demands immediate critical analysis and proactive assessment.

2. Background: historical development, factors, actors

While drones’ rise to prominence is fairly recent, the first models appeared as far back as World War I, when both the US and France developed unmanned airplanes capable of conducting automatic flight missions. Only during the last decade, however, have drones truly become a dual-use technology that can be used for both military and civilian purposes. The shift from exclusively military use to the civilian sphere began in 2005, when for the first time US military drones were used to search for survivors in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. Since then, the rapid development of UAVs has been fuelled by enormous technological progress in the design of batteries and sensors, automation, and the miniaturization of components.

Amazon’s 2013 initiative of product delivery by drone within 30 minutes, labelled “Prime Air”, can be considered the first step in using drones for revolutionizing the field of logistics. Not long after, almost all major logistics players (e.g. DHL) started to test drones’ potential to improve last mile delivery.

A recent study that sought to summarize nearly a decade of public debate on the subject of drones found that technical and regulatory factors tend to dominate the discourse. A clear expectation of economic benefits is the dominant argument in their favor, followed (less significantly) by generic expectations of societal and environmental improvements. Generally, the current debate on the subject is characterized by a juxtaposition of definite economic expectations (e.g. cost-savings due to automatization) with a variety of complex problems and concerns (e.g. safety and security, privacy, noise, legal issues). This reflects the uncertainty surrounding many of the specifics of drones’ potential impact on society and the environment.

Over the years, the topic has gained increasing attention among economic, political, and academic actors. Economically, the most prominent interested parties are logistics companies (DHL, UPS, DPD etc.); tech and e-commerce giants (Google, Amazon, Alibaba); and manufacturers of drone hardware. The latter include traditional aviation players (e.g. Airbus, Boeing) on one hand; and on the other – start-ups that receive tremendous amounts of financial capital, for instance from the automotive sector, and focus on seeking innovative business and market opportunities.

The political actors driving the global debate are the European Union (EU), the US, China, or Israel. The EU, for instance, has set the ambitious goal of becoming one of the global leaders of UAV deployment, accompanied by an expectation of far-reaching positive effects on the labor market. The European industrial policy clearly aims to capitalize UAV operations over the next few decades, as represented by the recent implementation of an EU-wide drone regulation which forms the base of creating a harmonized European drone market.

Furthermore, the topic of unmanned aviation has increasingly become the focus of academic attention. Though traditionally dominated by technical and engineering perspectives, the academic discourse has more recently been enriched by input from the fields of social science and the humanities.

In contrast to the growing focus on advanced ideas of potentially using low level airspace as a new layer of transportation in economic, political, and academic circles, the general public is still widely unaware of, and/or uninformed about, the issues involved. To this point, there is no discernible in-depth society-wide discussion on the use of lower airspace, and hardly any civic engagement in this area.

3. Current state of affair

Commercial drone applications become more common by the day, particularly in the field of sensing missions. Moreover, mainstream media coverage of delivery drones and air taxis is on the rise, which in turn raises public awareness of the technology and its applications. Nevertheless, the level of acceptance of drone transportation among the general public remains consistently low. In the latest representative survey in Germany, only 25 per cent of respondents agreed that drones should be used to deliver consumer goods and products; and only 21 per cent agreed that air taxis should be used for passenger transportation. The only exception is the use of drones for medical purposes, which has been embraced by almost two thirds of respondents of the survey in question. The main reasons for the skepticism towards drone technology are a perceived lack of usefulness and safety concerns. Overall, the European public does not consider drone-based delivery of goods – in contrast to their use for medical and emergency purposes – a top priority. Consequently, the critical issue of raising societal acceptance is gaining prominence on political and industrial agendas.

Besides improving public acceptance, another immediate challenge is the creation of Unmanned Traffic Management (UTM) with the aim of safely integrating drones into the airspace. Termed U-Space in the European context, such a system can be understood as a highly digitized, automated control environment that enables safe and efficient access to lower airspace for a large number of drones. In this context, current discourse on air traffic management infrastructure highlights a potential need for physical facilities on the ground, such as vertiports for landing and take-off and drone warehouses.

Current discourse on operational issues tends to focus on transportation for medical and humanitarian purposes, likely in light of the global COVID-19 pandemic, as well as greater public acceptance of these applications. As for consumer goods, early scenarios of large scale last mile delivery along the lines of Amazon’s “Prime Air” have given way to more life critical applications that are also quantitatively less invasive. There is no clear trend in the field of passenger transportation, as a variety of options (short distance travel, intercity transit, flying ambulances) are being discussed.

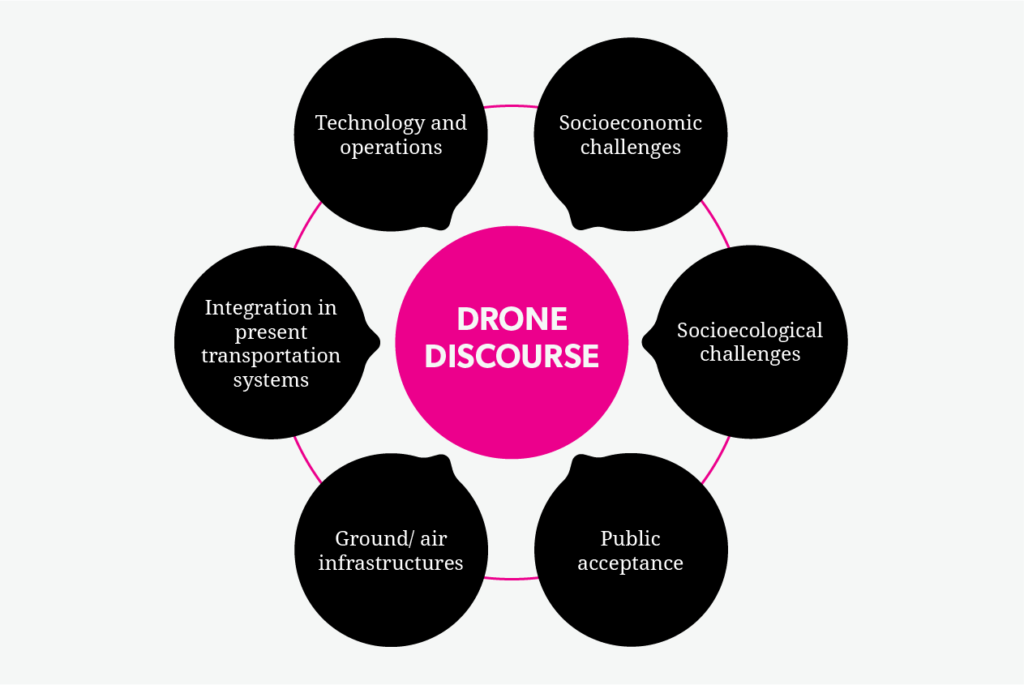

Figure 1: key aspects of the current drone discourse (own illustration)

4. Analysis and assessment of the implications of the current situation

Using drones for transportation purposes is an up-to-the-minute development that is expected to transform the transportation system and benefit society. This optimistic projection is conveyed in a set of narratives repeated not just by economic actors actively promoting the technology, but also by policy makers hoping to embrace a new economic sector. Common arguments on transportation drones’ positive implications are that delivery drones and air taxis would (i) reduce travel times, (ii) ease urban congestion, and (iii) be environmentally friendly.

However, these arguments are yet to be scientifically validated. The following section will provide a critical assessment of each of the three claims.

i) “Air taxis reduce travel time”

Once airborne, air taxis will no doubt be a fast mode of transportation, given that the aircraft bypasses the (congested) road system and flies by the shortest possible route towards its destination. However, in an urban context with a well-developed transportation system (as is the case in most European metropolises), travel time would only be reduced under specific circumstances. For instance, distribution density of vertical take-off and landing hubs (vertiports) must be equal to that of the existing urban railroad stations. Lower density of vertiports may even result in longer door-to-door travel times compared to conventional means of transportation.

In addition, the questions of how and where to implement the necessary physical infrastructure remain unsolved, especially in areas where space is already a limited resource. On top of this, insufficient air traffic management capacity (due to intensive drone activity) would drastically reduce any time saving involved.

In summary, the extent of travel time reduction from the use of air taxis can only be fully evaluated when taking into account the density of supplementary infrastructure, speed relative to that of conventional transportation, aircraft range, and local congestion levels. While in some scenarios air taxis may be ‘time-savers’, in others they may become ‘time traps’. Consequently, the extent of their benefit as a faster mode of transportation is uncertain. Only a few studies have incorporated demand sensitivity analysis and modelling that took into account technological and operational parameters. Further research is necessary in order to better understand the factors that influence the assessment of potential time saving (e.g. infrastructures, range, passenger/ parcel handling procedures).

ii) “Delivery drones and air taxis relieve road congestion”

From a technical standpoint, passenger and delivery drones, once airborne, would either bypass ground-based traffic congestion, or prevent congestion by moving part of ground traffic into airspace. With an average payload of up to 3kg, drones can theoretically make about 80% of all domestic parcel deliveries. However, a number of limiting factors casts doubt on the actual extent of potential ground traffic reduction.

Firstly, drones can’t (yet) conduct complex multiple deliveries, and hence can hardly be considered a serious competition for conventional logistics on the ground. Instead, drone deliveries may offer the greatest relative advantage in cases of remote individual deliveries or humanitarian scenarios. Both of these, however, account for only a marginal share of total traffic flow, so the drones’ potential for ‘tangible’ traffic reduction is limited. Beyond that, passenger drones’ maximum capacity of five passengers would severely limit their modal share. More critically, air taxis are also found to not alleviate road congestion in the transportation system as access and egress trips to vertiports will even slightly increase the total vehicle kilometers traveled by car.

Secondly, substitution effects only prevail under stable conditions of demand. The amount of parcel deliveries, however, is anticipated to increase tremendously, powered by economic growth and consumption patterns that fuel the fast-growing E-commerce business. Delivery drones themselves may indirectly facilitate the growth spiral of the E-commerce sector, especially if they eliminate the problems of unreliable and expensive last mile delivery. Improved customer experience and cheaper delivery fees are likely to increase online ordering by customers, which would in turn generate additional traffic flow. This would eventually lead to a classic rebound effect.

To summarize, drone-induced traffic reduction appears to be an intuitive solution to existing problems, yet the extent of actual benefits remains an open question. To assess these, we need a deeper understanding of i) precise substitution potential of various drone applications, and ii) drone-related (long-term) economic and behavioral effects. Future research would have to validate the substitutional effects of different drone-related scenarios, and discuss them in the context of recently reviewed transport planning strategies.

iii) “Drone transportation is environmentally sustainable”

The key argument stressing drones’ environmental benefit is that they are battery- powered, and thus avoid (local) pollution. Indeed, the technological development of (civilian) drones focuses on batteries. A recent paper however, advances the argument that any analysis of electric mobility needs to take into consideration factors such as electricity sources, use-phase energy consumption, vehicle lifetimes, and battery replacement schedules. In short, drones’ feasibility as a major new mode of sustainable transportation should be measured against the sustainable mobility paradigm.

A full life cycle assessment is required in order to evaluate the environmental friendliness of drones. Based on estimated energy efficiency and environmental costs, drones could then replace traditional modes of transportation wherever they are clearly more environmentally friendly. A thorough assessment of drones’ environmental friendliness thus needs to take a more comprehensive comparison approach against other modes of transportation. At present, such an assessment is impossible, based on currently available data and research. In general, drone technology may only have the potential to be more environmentally friendly than traditional modes of transportation, provided that the electricity powering them is generated entirely from renewable energy sources. In addition, drones’ batteries’ energy efficiency needs to be maximised; and the batteries themselves need to be recyclable or reusable in order to reduce emissions effectively. On the other hand, propulsion and vertical mobility are generally more energy-intensive than ground-based motion. It is therefore unlikely that in the near future drones will prove to be a more energy efficient option than existing transportation technologies.

Altogether, further scientific evidence is needed to demonstrate that they are an environmentally friendly technological alternative. In recent years, comparative studies of energy efficiency of conventional fuel-based versus drone-based electric transportation have been conducted within the framework of logistics research. The results suggest that drones can be efficient substitutes for conventional vehicles in the cases of one-item-per-trip deliveries (express, medical supplies). In contrast, drones are likely to be less efficient when it comes to delivering several packages that could be bundled on a route. However, findings from these pioneering studies are still partial, and hence insufficient for a general assessment of drones’ environmental friendliness.

5. Flying high? Final remarks

Drones are expected to become a “game changer technology” for the transportation sector, with the potential to revolutionise logistics processes and passenger transportation. While drones are unlikely to become a mass transit mode, there’s a high probability of drone applications flourishing in niche markets, e.g. express delivery of medical items or passenger transfers in certain scenarios.

Nonetheless, we are currently seeing that the potential effects of transportation drones tend to be oversimplified as being wholly beneficial. Hence, substantial scientific qualification is needed in order to better assess the benefits of various drone applications against potential rebound effects.

What’s more, there’s still a glaring lack of public awareness of the issues at stake, and of public participation in the debate on the subject. This is despite the fact that each single flight will instantly affect the public (as these take place in public space), and despite the historical significance of extending public space towards lower airspace. Instead of initiating an open debate on the use of lower airspace, major economic, political, and regulatory actors either predominantly address public safety concerns, or (secretly) hope to convince the public by demonstrating the technology’s benefits once it is implemented. This approach, however, partially ignores multiple issues (noise, privacy, environmental implications) revealed by recent research on technology acceptance.

Once drones become more visible, the use of lower airspace may turn into a hot socio-political issue. Policymakers dealing with the issue must balance various stakeholder interests with overarching social goals (sustainability, justice, equality). A recent study recommended a set of 12 research-based actions that try to achieve this balance, with the aim to provide a framework for socially, economically and ecologically feasible use of transportation drones.

This is only the starting point for initiating a debate with the aim of creating maximum societal acceptance and legitimacy. This should be achieved via a combination of proactive technology assessment and the facilitation of real-world laboratories including open public participation and transparent dissemination of information.

————————————————————————————————————————————————–

This backgrounder is published in the framework of the European-Israeli Forum for Environment and Sustainability, a joint initiative by the Israel Public Policy Institute (IPPI) and the Heinrich Böll Stiftung Tel Aviv.

The opinions expressed in this text are solely that of the author/s and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Israel Public Policy Institute (IPPI) and/or the Heinrich Böll Stiftung Tel Aviv.

Share this Post

Navigating the Future: Germany's Autonomous Driving Act

The Autonomous Driving Act took effect in Germany on July 28, 2021, introducing significant and comprehensive amendments to…

How does the DSA contribute to platform governance and tackle disinformation?

Introduction The adoption of the Digital Services Act (DSA) has been a welcome landmark step in European digital…

AI: A New Frontier in Art Authentication?

Authors: Eduardo Magrani & Francesca Portante d’Alessandro How is artificial intelligence reshaping art authentication? The image of the refined…