A Call for a Value-Driven Approach to ‘Digital Sovereignty’

Share this Post

The Internet has been labelled as an independent and universal space throughout the 1990s and until today many believe it should be run by a special set of rules. Concrete examples include cryptocurrencies (e.g. Bitcoin, Ethereum) and ‘self-sovereign’ digital identity management. However, the discussion whether countries should pay more attention to ‘Digital Sovereignty’ has intensified over the last decade. In the 2020 programme for Germany’s Presidency of the Council of the European Union (EU), it proposed that Digital Sovereignty should become a guiding objective (‘Leitmotiv’) for future policies. Some believe it is necessary to reassert authority over the internet and protect citizens and businesses from the manifold challenges to self-determination online. The dependency on large corporations and their platforms to engage in all aspects of social and economic life was already much discussed before the pandemic, but has only increased with the need for physical distancing. Data is vital to understand and mitigate the impact of SARS-CoV-2 and the reliable accessibility of data infrastructure is a key concern as the ‘Digital Divide’ grows. Unresolved national security concerns, such as the persistent threats of surveillance and cyberattacks, combined with the inability of the multi-stakeholder community to address them fuel the desire of many to ‘take back control’. The simple idea that sovereignty needs to be perfectly aligned between national territory and cyberspace is appealing at first. However, it undermines the privileges of those who are fully accustomed to the social and economic benefits of an open internet that enables cross-border exchange.

What is Digital Sovereignty?

At the moment, there is no universal definition of Digital Sovereignty and the concept is mainly used to frame political demands. In a speech from 3 February 2021 EU Council President Charles Michel defined the quest for Digital Sovereignty as essential for ‘strategic autonomy’, which […] ‘means more resilience, more influence, and less dependence.‘ In a recent report the EU Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA) linked the concept of Digital Sovereignty to Digital Strategic Autonomy. It consists of the

- personal aspect, such as data protection and privacy;

- industrial aspect, such as confidentiality and security for a data-driven industry;

- political aspect, such as autonomy and cybersecurity for EU institutions and Member States.

ENISA defines ‘digital strategic autonomy as the ability of Europe to source products and services that meet its needs and values, without undue influence from the outside world.’ Here – as for any other political actor – this describes the capability to operate as an autonomous society in the 21st century. To give a concrete example, recently a discussion emerged in the Netherlands on whether the outsourcing of core management tasks of mobile telecommunication networks results in concerns of intrusive surveillance by Chinese entities. Even senior members of governments were using this mobile network, while it was not clear how the national provider could ensure that there was no unwanted surveillance by Huawei.

Arguably, Digital Sovereignty and strategic autonomy are particularly urgent for those political entities that pursue models of differentiated political integration, such as the EU or the United States. Citizens fear the loss of control over their data, but also of their capacity to innovate. Additionally, with the increased dependence on digital platforms developed and maintained by private corporations following their own rules, there are concerns about the relevance of democracy, human rights and the rule of law. At the same time questions emerge how new regulatory frameworks of the EU such as the Data Governance Act, the General Data Protection Regulation, or the proposed regulation of Artificial Intelligence affect international trade.

Conceptual approaches to ‘Digital Sovereignty’

A traditional approach to sovereignty can be found in the work of German philosopher Georg Friedrich Wilhelm Hegel, who suggested that it needs to manifest through an individual with absolute powers, such as the Prussian monarch. Later in the 19th century legal scholar Georg Jellinek proposed the ‘three elements doctrine’. Accordingly, territory, population and sovereignty are essential to becoming a state. The element of sovereignty has an internal and external dimension and the sovereign has the duty to control both. As long as all three elements are intact a state is formally considered independent from other political actors. All states have equal rights, regardless of the size of their population and territory. However, with more political and societal interdependence and enhanced cooperation among states, as well as the division of labor and the globalization of the economy, Digital Sovereignty has become a much more encompassing concept. Today, it is not only addressing issues relating to ‘hard infrastructure’ such as internet communication, connection and technological capability. Rather, it also relates to the digital transformation of society as such.

Back to protectionism?

This interconnectedness and interdependence challenges command and control structures which are central to traditional conceptions of sovereignty, and questions around the feasibility of networked governance. At the moment, states struggle to translate the rule of territorial sovereignty into the 21st century. One of the main concerns about Digital Sovereignty is that it will result in the fragmentation of cyberspace, or the emergence of the ‘splinternet‘. In 2018 O’Hara and Hall already argued that there are four internets, whereas the permanent tensions between the People’s Republic of China and the United States about issues such as the governance of social media platforms like TikTok, or the role of corporations such as Huawei in future 5G networks do little to reverse this trend.

This is particularly problematic for European countries, which have to review their strategic dependency on cost-effective solutions. At the same time projects to establish independent European cloud infrastructure such as GAIA-X progress slowly and it remains vague who should be able to shape them. The role of non-European partners such as Amazon and Microsoft is controversial and European states are also concerned about the power balance between themselves. Some states such as Germany seem not to have the patience for lengthy discussions, and rather turn to traditional means when establishing their own federal cloud infrastructure. However, this increases their dependency on the private sector, which is a trend that can also be witnessed in states such as Israel.

While protectionism might appear as an attractive political alternative that allows to avoid the cumbersome process towards multilateral agreement, it cannot deliver sustainable long term solutions. With the scale of specialization required to effectively develop and maintain competitive infrastructure in the Digital Age, it is increasingly important to be able to pool skills and resources. This can only be achieved on the basis of shared objectives and values between states and societal stakeholders. Their establishment can start with an agreement on detailed standards, preferably in the form of multilateral treaties on the level of international organizations such as the Council of Europe. The Council has a long-standing tradition of addressing data protection and cybersecurity. It is currently working on new standards for Artificial Intelligence. The conventions of the Council are also open for non-member states all across the world.

Why a value-driven approach matters

What the European Union – and in fact all political actors – need are overarching strategies that define how the digital domain integrates into policies on all governance levels. This means that future policies for trade, industrial development, or security accept that both the physical and virtual domain require an overarching and holistic strategy. For instance, organized crime such as drug trade needs to be tackled with a plan that addresses national and international smuggling, selling of drugs in cities and public spaces, but also online via ‘Dark Web’ platforms. All these elements are part of the same problem, and some only exist online.

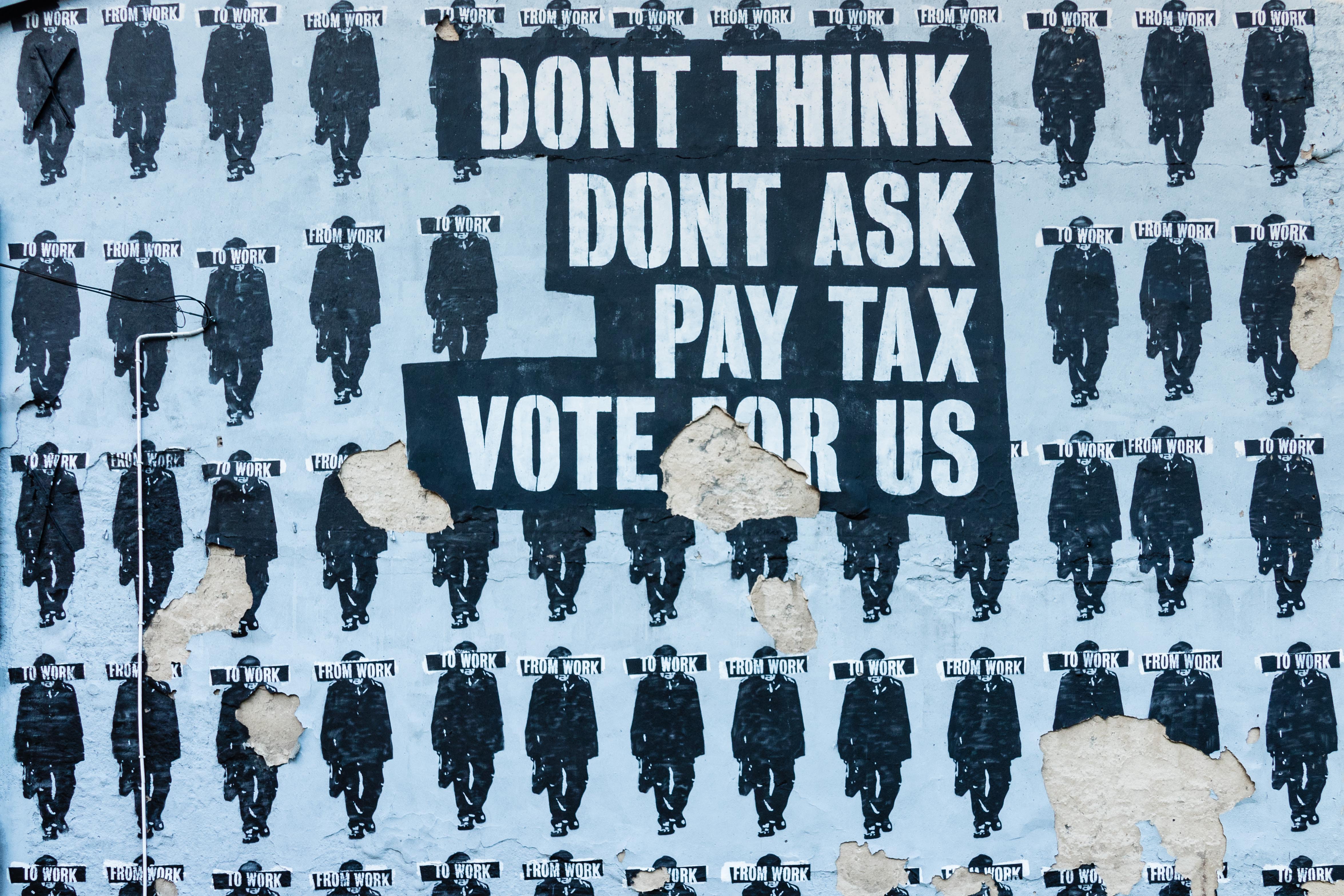

Simple designs for such governance strategies mirror the physical and territorial borders of countries into the digital domain. This results in re-territorialization of the Internet (e.g. Russian Federation), extended Internet shutdowns and censorship (e.g. India, Uganda) or increased surveillance and control of social life (e.g. People’s Republic of China). While this seems to work from traditional governance perspectives as advanced by Hegel, it can hardly be a valid option for European states, the United States and many others. Their social and economic prosperity is closely tied to the ability of operating cross-border. Their citizens expect a large degree of autonomy that is no longer limited by territories. If it is desirable to keep and expand these abilities throughout the Digital Age, more agreement on multilateral governance frameworks is essential. Such frameworks have to be principle-based to provide long-term stability. Ultimately, we should not only care about ‘hard infrastructure’ and technical capabilities, but explore how values effectively guide the efforts to create, operate and maintain them.

————————————————————————————————————————————————–

The Israel Public Policy Institute (IPPI) serves as a platform for exchange of ideas, knowledge and research among policy experts, researchers, and scholars. The opinions expressed in the publications on the IPPI website are solely that of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of IPPI.

Share this Post

Updating Democracy for Future Generations: Adding a Fourth Branch to the Separation of Powers Model

Over the past two decades, political science has engaged in a lively debate about the “presentism” of democracies,…

The Transition to Electric Vehicles in Israel

An electric vehicle (EV) operates on electricity, unlike its counterpart, which runs on fossil fuel. Instead of an…

Towards Democratic Innovation in Israel: The Case for Citizens' Assemblies

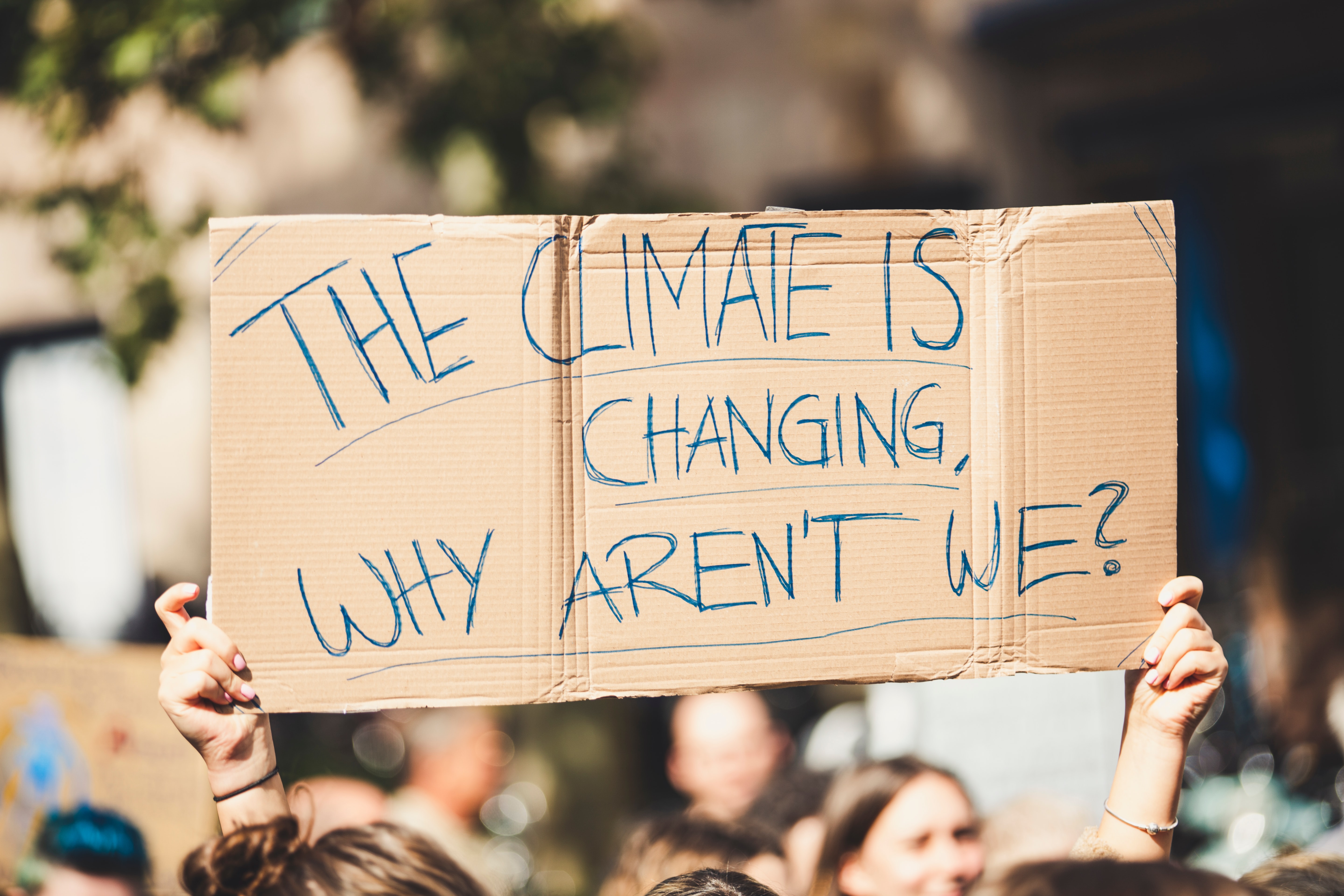

Citizens’ Assemblies as Instigators for Climate Action The erosion of liberal democracies is arguably a sign of our…