What role could off-shore wind energy play in Europe's energy transition?

Share this Post

With a goal to reach climate neutrality by 2050 and faced with a new geopolitical situation following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the EU will need to speed up its transition to renewable energy while phasing out the use of Russian oil and gas.

In May 2022, four EU member states, Denmark, Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands, all bordering the North Sea, held the North Sea Summit in Esbjerg, Denmark’s leading offshore harbor. President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen and the Commissioner for Energy, Kadri Simson, also attended the summit.

At the summit, heads of government from Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium and Denmark signed a joint declaration, The Esbjerg Declaration, that will make the North Sea the green power plant of Europe, focusing on offshore wind and green hydrogen.

In the Esbjerg Declaration, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, the Netherland’s Prime Minister Mark Rutte, Belgian Prime Minister Alexander De Croo and Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen pledged to increase their countries’ total offshore wind capacity in the North Sea to at least 65 GW by 2030 and at least 150 GW by 2050, which is more than half of the capacity needed to reach EU climate neutrality.

The European Commission’s ambition is to have at least 300 GW offshore wind by 2050 to achieve its goal of climate neutrality.

Offshore wind: A competitive renewable energy source

Over the past three decades, offshore wind energy has become a competitive, large-scale renewable energy source with costs of European offshore wind now lower than new gas, coal and nuclear power plants.

A lot has happened since 1991, when the world’s first offshore wind farm started operating. Eleven wind turbines with a capacity of 450 kW each, or just under 5 MW in total, were erected in shallow waters off the coast of Vindeby, Denmark.

Over the following decades, the offshore wind industry scaled up and significant technological advances were made. The levelized cost of energy (LCOE) was reduced substantially as processes were streamlined, the supply chain was industrialized, and manual processes were automated.

Today’s large offshore wind farms, the biggest with capacities of over 1 GW, are placed further from shore and at much deeper waters than in the past, and this requires much larger wind turbines with longer blades.

Vestas, the Danish wind turbine manufacturer, will have its V236-15.0 MW offshore turbine installed at the Østerild test facility in the north of Denmark in the second half of 2022, while serial production is planned for 2024. With a height of 280 meters and a production output of 80 GWh per year, this prototype is the tallest and most powerful wind turbine in the world.

The North Sea’s potential

The North Sea spans approximately 570,000 square kilometers and with vast wind resources to harvest, it offers tremendous potential for the countries along its shores.

Today, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium have approximately a total of 15 GW of installed offshore wind in the North Sea and will need to increase the current capacity ten-fold by 2050 to reach the goal set out in the Esbjerg Declaration.

Each of the four member states already has ambitious national targets for offshore wind capacity:

- Denmark has currently installed 2.3 GW of offshore wind capacity. By 2027, a further 1.35 GW will be added, while political decisions have been made to add a further 15 GW of offshore wind by 2040, including 2 GW in the Baltic Sea. The Danish Government has also proposed a further 1-4 GW of offshore wind capacity before the end of 2030.

- In Germany, 7.7 GW offshore wind capacity has been installed and the country aims for 30 GW of offshore wind by 2030, 40 GW by 2035 and 70 GW by 2045.

- The Netherlands has installed some 2.5 GW offshore wind capacity. The Netherlands has set a target of 21 GW offshore wind capacity around 2030 and expects a minimum need of 38 GW in 2050.

- Belgium aims to double its offshore wind energy production capacity within the next 10 years, to reach a target of 8 GW offshore wind capacity by 2040.

If a combined capacity of 150 GW in the North Sea is reached, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium will provide green electricity for 230 million Europeans.

At the same time, the Esbjerg Declaration will enable decarbonization of hard-to-abate sectors (those which are difficult to transition due to high costs or insufficient technology) with green hydrogen, e.g. shipping, aviation, heavy industry and heavy vehicles. The plan is for offshore wind to be used at large-scale onshore and offshore production of green hydrogen with combined targets of approximately 20 GW production capacity by 2030.

Green hydrogen is produced by splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen using renewable electricity, for example from offshore wind farms, in a process called hydrogen electrolysis.

Denmark has a goal to have 4-6 GW electrolysis capacity by 2030 for green hydrogen production, which will enable reductions of 2.5-4 million tons of CO2 in 2030. Germany aims to achieve an electrolysis capacity of 10 GW by 2030 while the Dutch government has set a national target of 4 GW electrolysis capacity by 2030. Belgium is working on establishing an energy hub, expected to include the production of green hydrogen.

Energy islands in the North Sea

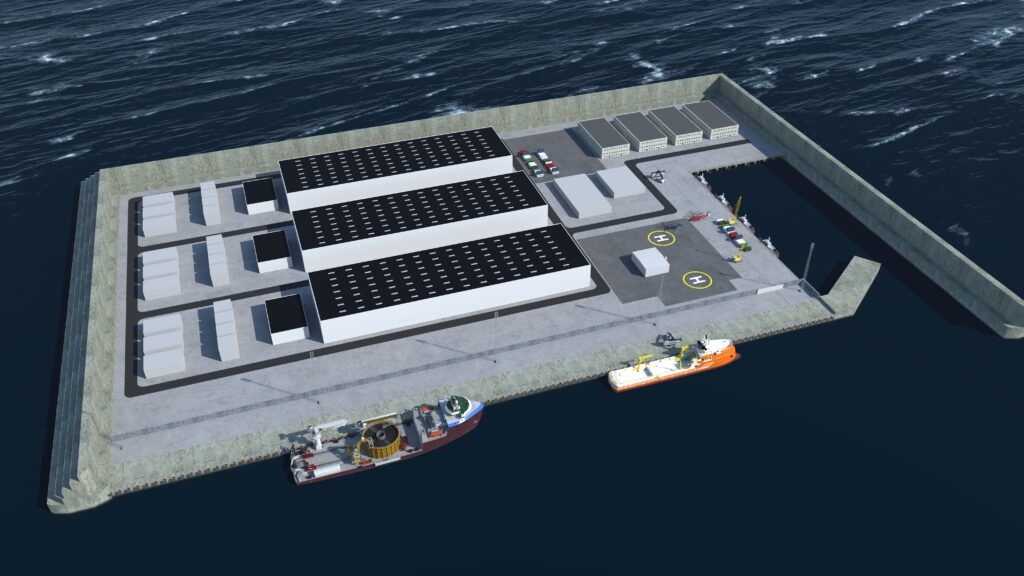

To harvest the full potential of the North Sea while optimizing how offshore wind resources are used, gigantic energy infrastructure systems, or energy islands, are required. Energy islands are artificial islands that can be connected to surrounding offshore wind farms and the electricity grid of other countries. They may also be hubs for energy storage or for conversion of green electricity into green fuels for heavy transport such as aviation and shipping, through Power-to-X technologies.

Illustration by Danish Energy Agency

Denmark has already pledged to build an energy island in the North Sea, the first-of-a-kind in the world and the largest construction project in Denmark’s history. The energy island, which has a total area of at least 120,000 square meters and will merge up to 10 GW of offshore wind farms, will gather and distribute electricity from the surrounding offshore wind farms, distribute the electricity among the North Sea countries connected via the grid and can be used to produce green fuels.

In addition to the joint Esbjerg declaration, ministers of energy from Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium signed an agreement to cover, among other things, cooperation on connecting and maximizing capacity on the first energy island, plan the establishment of another energy island or hub in the North Sea, work for faster approval processes both nationally and in the EU, and ensure more EU funds for offshore wind projects to reduce risks for investors.

The purpose of this agreement is to establish interconnections between the energy island in the Danish zone of the North Sea and the other countries via bilateral agreements, enabling export of renewable electricity to neighboring countries and at the same time supporting the green transition in the EU while enhancing energy security.

During the Esbjerg Summit, Denmark also signed bilateral agreements with the three other countries:

- Denmark and Belgium signed an agreement to sell shares of Danish renewable energy to Belgium with funds from the sale to be used to co-finance the costs related to the energy island, production of renewable energy and green gasses.

- Denmark and the Netherlands signed a ministerial endorsement regarding a possible interconnection between the Danish energy island and a Dutch energy hub at a later stage of the energy island in the North Sea, possibly around 2035. The scenarios will be further analyzed by the national transmission system operators (TSOs), the Danish national transmission system operator for electricity and natural gas, Energinet, and the Dutch national transmission system operator, TenneT, in 2022.

- Denmark and Germany signed a letter of intent regarding cooperation on Power-to-X and sector integration, setting a framework for future cooperation to accelerate the transition from imported fossil fuel to European renewable energy.

Once fully developed, the North Sea Green Power Plant of Europe will consist of multiple connected offshore energy projects and hubs, offshore wind production at a massive scale as well as electricity and green hydrogen interconnectors and will be able to provide green electricity to up to 230 million European households.

Further readings

- Bilateral energy island cooperation in the North Sea: https://en.kefm.dk/Media/637884825620650715/NorthSea_Fact4_EN_180522.pdf

- The Esbjerg Declaration:https://en.kefm.dk/Media/637884571703277400/The%20Esbjerg%20Declaration%20(002).pdf

- How the offshore wind industry matured: https://orsted.com/en/insights/white-papers/making-green-energy-affordable/1991-to-2001-the-first-offshore-wind-farms

- Denmark decides to construct the world’s first energy island: https://en.kefm.dk/news/news-archive/2021/feb/denmark-decides-to-construct-the-world%E2%80%99s-first-windenergy-hub-as-an-artificial-island-in-the-north-sea

The opinions expressed in this text are solely that of the author/s and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Israel Public Policy Institute (IPPI) and/or its partners.

Share this Post

Eroding Trust: Contact Tracing Technologies in Israel

Contact tracing technologies can potentially help health organizations and governments stop the spread of COVID-19 by finding and isolating…

Transitioning to a Circular Economy: What are the Challenges?

The expected increase in world population to 9.7 billion world citizens in 2050, alongside a growing middle-class, is leading to…

Unfolding Energy Poverty in the European Context

According to the European Commission (EC), before the pandemic outbreak, at least 34 million Europeans could not heat their homes…